Bound Voices #004 — A Conversation with Nate McCall

On craft, permanence, and the living art of the book.

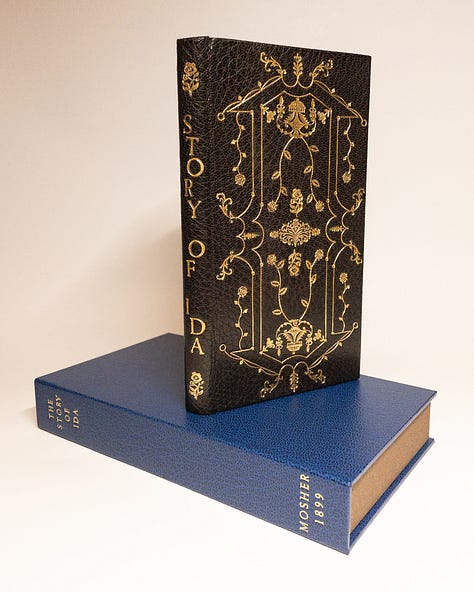

In an age defined by screens and instant ephemera, Nate McCall spends his days at the opposite end of time. Inside his McCall Co. Bindery workshop in the Pacific Northwest, he restores, rebinds, and reimagines books — one at a time — with an artistry that honors centuries of craftsmanship.

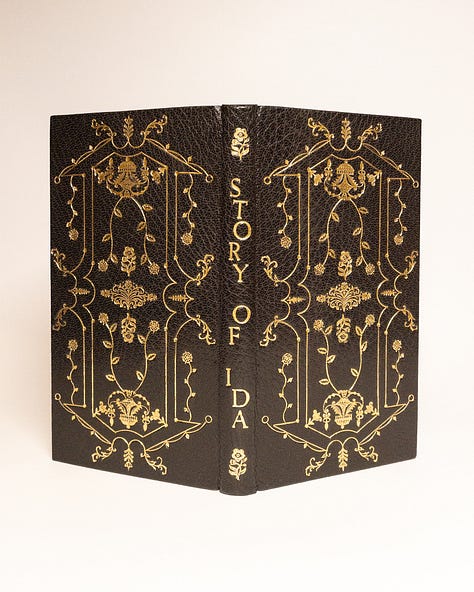

McCall’s bindings feel like meditations in leather, paper, and gold. Each work is both an act of preservation and a declaration that the book, as an object, still matters. His clients range from collectors and libraries to artists and presses like Ink & Ribbon, for whom he will bind the Fine Editions series — our attempt to slow the press and make poetry tactile again.

In this conversation, McCall reflects on how materials shape meaning, why permanence still matters, and how tradition lives on through the hands that keep it.

G. K. Allum: You describe yourself as a craftsman who works at the intersection of art and function. When you begin a new binding, where does the process start — with the book’s content, its form, or the imagined hands that will one day hold it?

Nate McCall:

Most of my commissions start with at least a general design direction from the client, but occasionally I get lucky enough to be given free rein. When I’m working with a client’s desires, I do my best to honor their requests and the content of the book, while adding my own creative touch. When I can do whatever I want, I first decide if I want to do something modern or based on the time period of the book. I’ve really become a big fan of modern bindings on antiquarian books — the words of the past still affect us, so why can’t they influence our art? As well, a book’s binding is a part of its history — an old book will often go through several bindings in its lifetime, often 200–300 years between — so leaving evidence of a modern brain’s interpretation of the text is something I think is valuable for future readers and collectors.

So I guess to answer your question, all three!

G. K: Many of your bindings feel like collaborations between material and ideas. How do you choose your materials — leather, cloth, paper — and what guides those aesthetic decisions?

Nate:

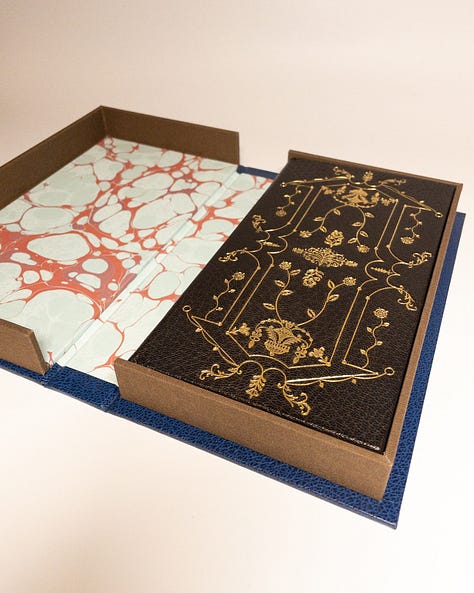

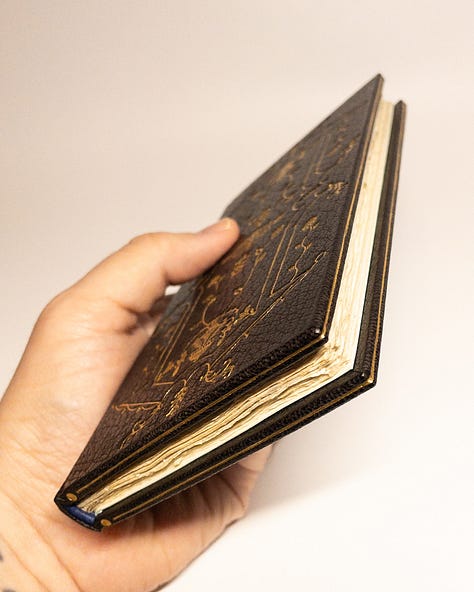

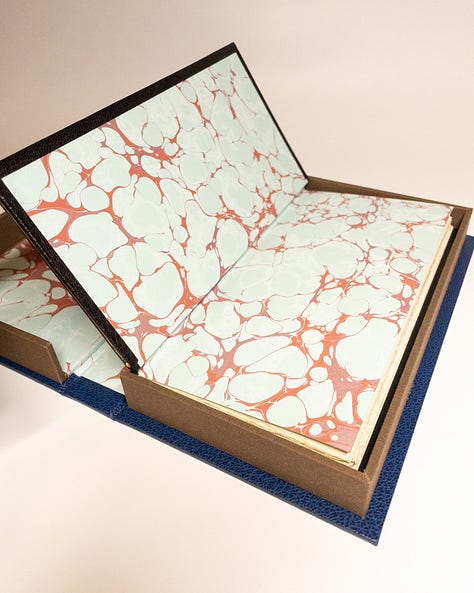

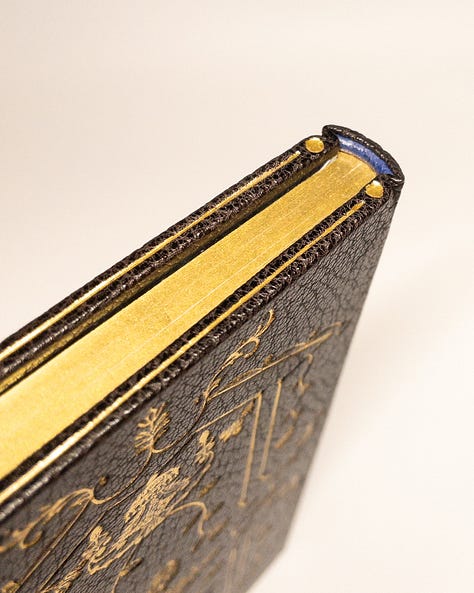

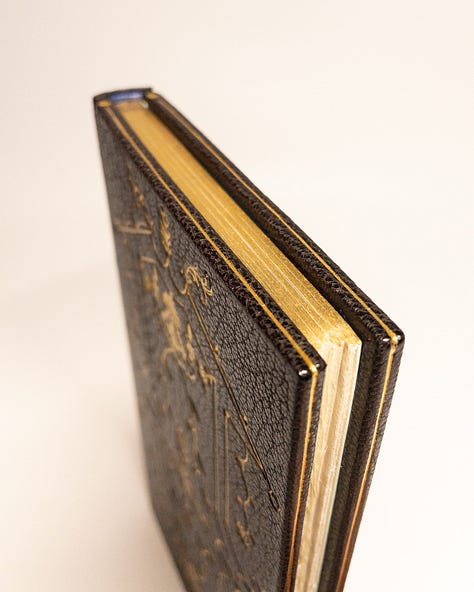

The planned final look of the binding is definitely the main driving force behind those decisions. What techniques do I plan to use to decorate; do I want it to look more traditional or modern; do I want to experiment or do something tried and true? It’s quite remarkable the effect a leather’s texture can have on a binding. Super smooth calf can have unusual textures pressed into it and can create some really amazing looks. Heavily textured goat can make gold tooling look that much more elegant. And there’s something to consider for everything in between.

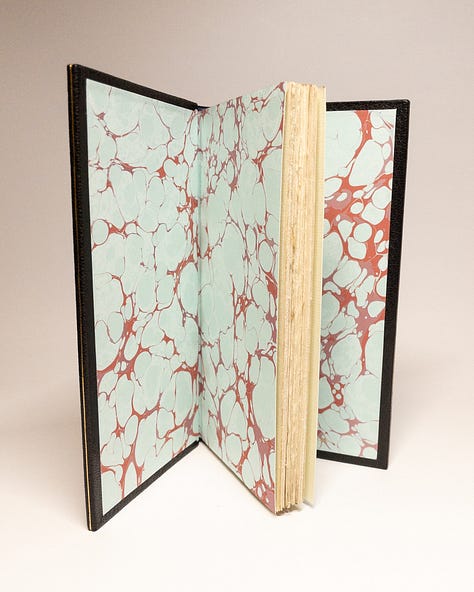

The materials I use on the interior of the book are just as important. Whether I’m using paper, cloth, or leather, it’s important that the feel of the binding is continued onto the inside of the book. Sometimes these decisions are made at the beginning of the binding process, in which case I need to make sure I have a very clear vision of what I plan to do, but often the interior is one of the last things I work on, which allows for the perfect match once the exterior is designed and finished.

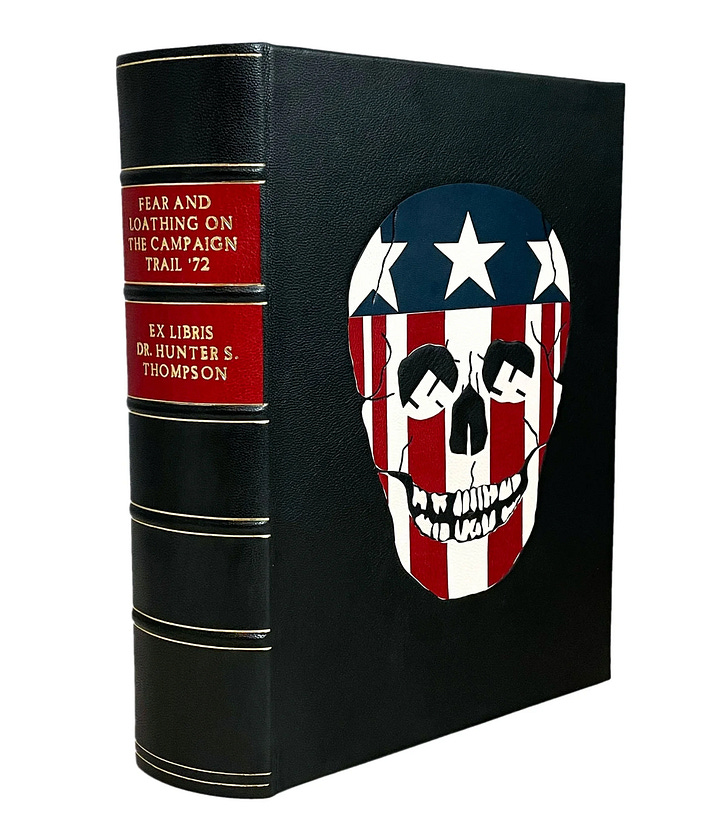

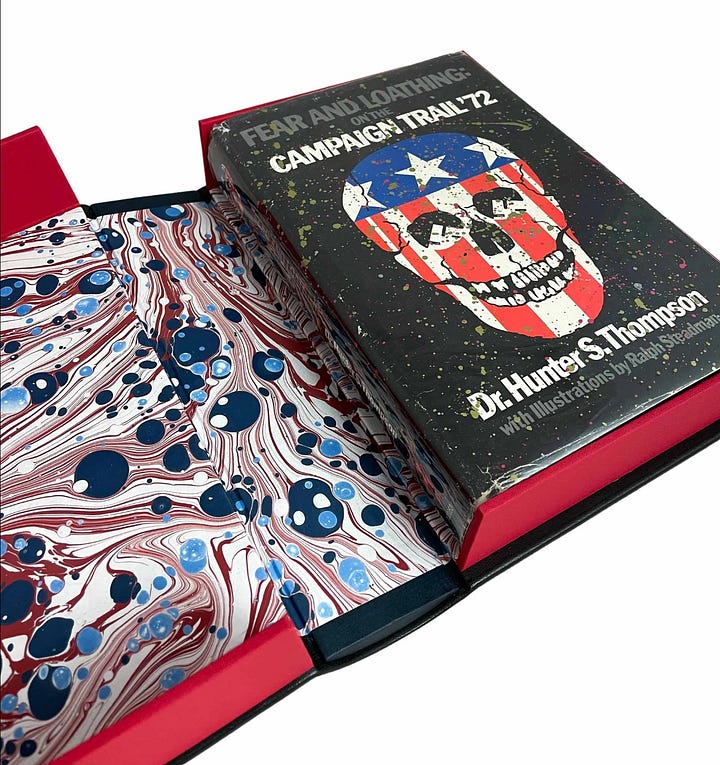

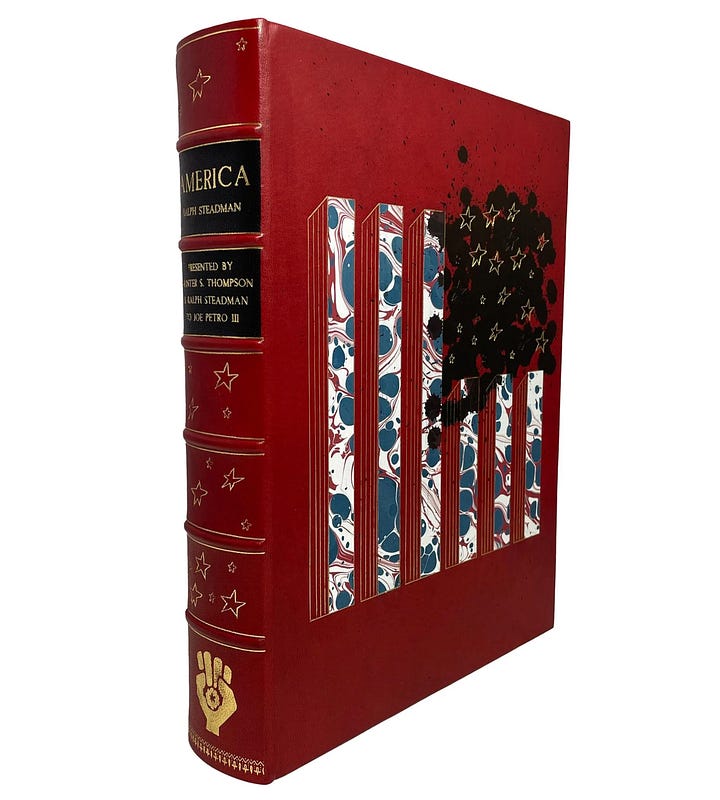

G. K: You’ve worked on extraordinary literary projects — including Hunter S. Thompson collections inspired by Ralph Steadman’s artwork. What did those projects teach you about storytelling through design and physical form?

Nate:

What I love about Ralph Steadman’s art is that it’s so clearly representative of the subject matter of the book it was created for, though still somewhat open to interpretation. Well known images and symbols are combined in a way that someone can gather meaning in just a quick glance. I admire art that can accomplish that, and while I’m always a fan of obscure and esoteric symbolism in art, sometimes I enjoy just being blunt.

G. K: Bookbinding has always balanced utility and beauty, but today the book itself can feel endangered. What keeps you inspired to make objects that defy the digital world?

Nate:

Frankly, physical books will likely outlive digital information. While the internet will probably exist in some form for at least a good while, under capitalism nothing that people “own” or have access to online is safe. Movies, video games, and books that have been purchased can disappear at the change of a contract or after a merger. As another example, I had tons of great photos of my early 20s on MySpace. I thought they were safe, but after the site was redesigned, all of those photos were just deleted, and I’ll never see them again.

A well bound book will preserve written and visual information as long as that physical object exists, which can be many centuries if properly cared for. Beyond that, a finely bound book is just a joy to hold. The textures, the shapes, the smells; far more worthwhile to hold than a phone or other digital device!

G. K: For poets and small presses like Ink & Ribbon, the binding is often the final act of faith — the moment words become real. What advice would you offer to publishers or artists who want to honor that moment?

Nate:

Do it right. A lot of modern physical publishing almost feels like an afterthought — aesthetics over quality. Hardcovers are basically upcharged paperbacks. Paperbacks are just glued paper (and often printed on paper full of acid that will eat itself away). As I mentioned above, if you care about the words you are publishing, a well bound book is what is going to make sure those words live on.

I have a collection of books on topics that seem mundane, but they are housed in beautiful fine bindings. Despite my personal lack of interest in the subject matter, they clearly meant something to their previous owners, and so they mean something to me. I’ll probably never read them, but perhaps they will be infinitely valuable to a future historian.

G. K: You’re part of a long lineage of binders and artisans. Do you see your work as preserving a tradition or reinventing one?

Nate:

I’d say a combination of the two. While bookbinding may feel like a dead or dying craft to the average reader, it is a tradition very much alive, and like any good tradition, it is evolving with every new generation of bookbinders. Some of the incredible techniques and styles that you see now in bookbinding would never have been seen 100 years ago, but are still very clearly part of the same tradition. It’s easy to see ourselves as the endpoint of something — e.g. the idea that we are the endpoint of evolution — but the reality is, we are moving through history, and the inventions we create now may be the traditions of the future.

G. K: Finally, if you could bind any text, from any era, for yourself alone, what would it be, and what would it look like?

Nate:

This is honestly a pretty long list, but probably my first choice would be a hand-illuminated medieval manuscript, and I would give it an elaborate mosaic style binding.

Editor’s Note:

Speaking with Nate, I was reminded that the book is not a relic — it’s a ritual. His work closes the distance between touch and thought, between word and world.

As Ink & Ribbon begins its Fine Editions series, there is no more fitting partner than the craftsman who binds art to time itself.

Further Reading:

Bound Voices is an ongoing series from Ink & Ribbon Press, a nonprofit publisher devoted to craft, discovery, and the permanence of the printed word.

Subscribe to The Inkwell for more conversations with the poets, printers, and artisans shaping the art of language today.