Bound Voices #003: A Conversation with Isaiah Freeman

Mapping the creative soul: on poetry, poetics, and the Ladder of Poetry.

What makes one poet search for essence while another strives for form? Why do some work through instinct and others through design?

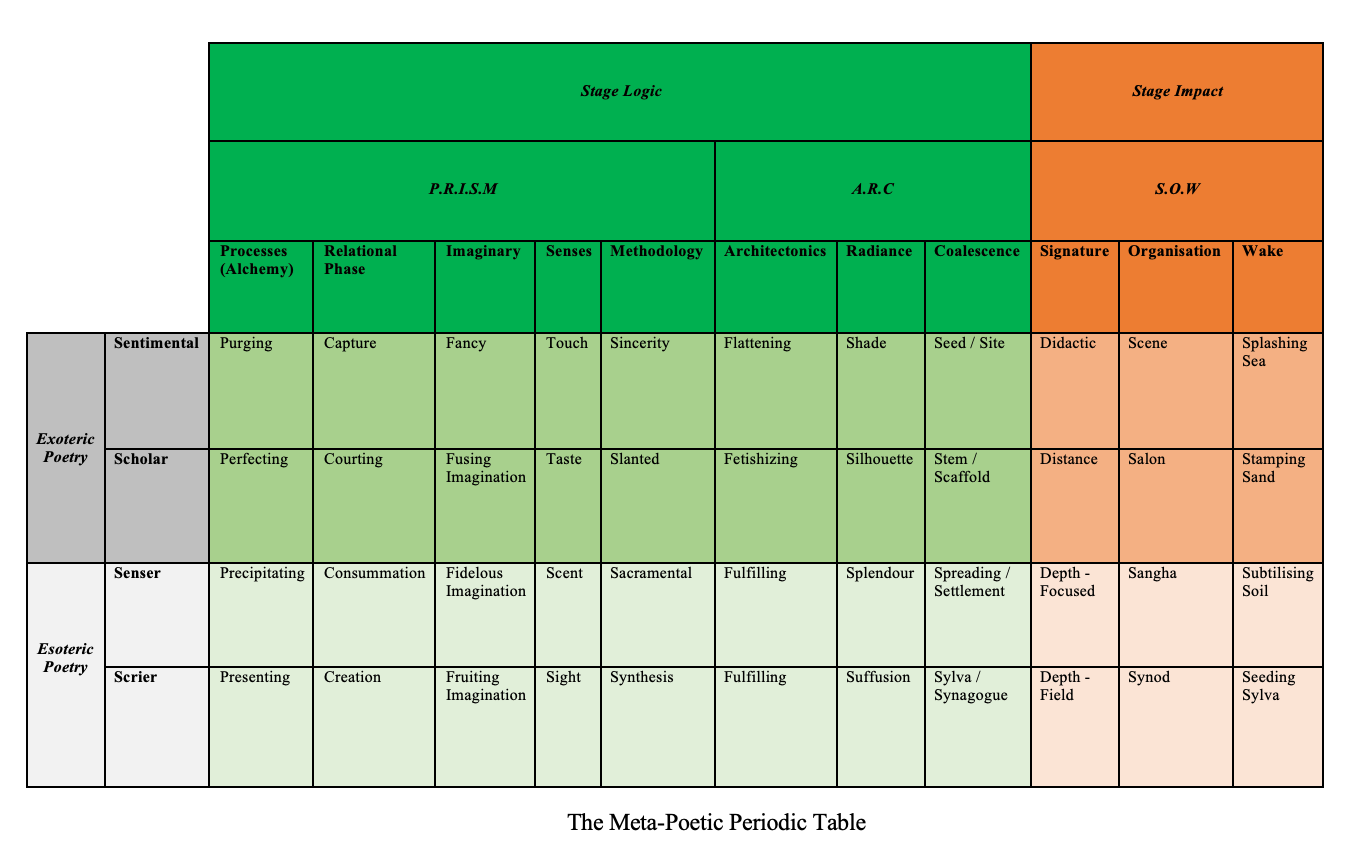

For Isaiah Freeman, these questions became a calling — one that led to the creation of The Ladder of Poetry, a philosophical and artistic framework that seeks to understand how poets evolve through different creative stages.

Based in Fremantle, Western Australia, Isaiah is both a poet and an English teacher — roles that merge seamlessly in his work on Essential Poetry, a Substack devoted to craft, consciousness, and community. His writing doesn’t just analyze poetry; it seeks to re-enchant it, to reveal the hidden architecture behind the art we often treat as mystical.

In this conversation, Isaiah speaks about the origins of his meta-poetic system, the tension between feeling and framework, and how understanding our creative “telos” might deepen, rather than constrain, the poet’s freedom.

G. K. Allum: Your framework, what you call a meta-poetic system, is remarkably intricate, drawing from philosophy, archetypes, and literary tradition. Before we dive into the theory, I’d love to understand where it began. Was there a particular moment, frustration, or creative question that made you want to “map” poetry in the first place?

Isaiah Freeman:

I’ve always liked to understand things deeply, and connect the philosophical dots. Especially things I care about. It was an insight for me when I joined a poetry community and found a poetry mentor at the start of the year to discover that many poets just like the instinctive chaos of the creative process and don’t feel the need to chart and map things out. That was probably a key event – seeing how different other poets are to my approach – that helped shape this ladder, which aims to help poets understand each other. I also found some poets like Shakespeare and Blake to be doing things I couldn’t understand, that also seemed different from me and the poetry community at large. So the differences in poetry approaches was becoming clear to me when I first joined these dots.

G. K: You’ve taught, written, and thought deeply about literature, but you’re also a practicing poet. How has your own writing life informed this system? Do you see yourself as more of an architect of ideas or as someone trying to make sense of the chaos of creativity from the inside?

Isaiah:

I think I’m at the sensing stage, working with spiritual essence. I always write to capture some haunting whisp that seems important to me in a way I can’t fully describe. I think Wordsworth does this well, and Keats. But I always felt like an alien because of this. So a sense of my difference definitely informed the system. I think it coalesced because I was trying to make sense of how creative approaches (or ‘poetics’, to use the academic term) can differ so much, and people clearly have such different beliefs and experiences around the process. I thought it would be cool to bring it together into a meta-poetic system, which I hadn’t seen done before. Usually people create their own poetics in isolation, or in opposition to another poetic approach – they don’t try to put the puzzle pieces together, to use a simple image.

G. K: You’ve described a kind of deep structure or “telos” in creative life — that each poet’s work is drawn toward a particular purpose or stage of development. I’m fascinated by that idea, but I wonder: does identifying those stages risk constraining a poet’s freedom, or can structure actually expand it?

Isaiah:

I think there are structures that can easily constrain a poet’s freedom. That’s when workshops with a particular style or way of doing things chafe. I think the stages I describe are too general for that to happen. They’re basically just saying if conveying emotion sincerely is your tendency then you’re probably at the sentimental stage. Each stage is equally valid by the way, because every stage tends to attract a certain readership, and we want poetry to reach as many people as possible. But I digress. I think understanding roughly what you’re already drawn to can sharpen your instincts rather than constrain them. It’s not prescriptive or a pigeonhole. Do what you like. It’s more just trying to get people to think about what really excites and calls to them. To see what they’re already drawn to. For some that’s crafting something really polished from a formal point of view. For others its cathartically purging something. For me it’s essence. So far I’ve found that artists resonate more with one stage than others. If you know you want to craft something polished then the system encourages you to become more versed in tradition and join workshops and own that. Want to create something cathartic? Then you don’t need to sound clever or do the formal polish thing. You can if you want to, but you don’t need to. What you’re doing is just as valid.

G. K: Many poets and artists are instinctive creatures — they work through emotion, accident, and intuition. For those who don’t think in systems or frameworks, how might your model actually help them? Could you share an example of how a poet or artist has used it in practice — a moment where it tangibly changed how they worked?

Isaiah:

Good question. Yes, emotion, accident and intuition are all parts of the mysterious process. But there is an organising force going on that uses the emotion and accident and intuitions, no? Otherwise it would be incoherent and unrecognisable. But we have styles, patterns emerge in our work. That’s because there is some organising force in us. Think of it like a magnet that looks for the right material to match what it’s seeking. Seeking without knowing what it is seeking, of course. That magnet is what I’m talking about. Some of us have magnets for emotion, others for aesthetics, others for essence, and the freaks like Shakespeare and Blake for vision.

I worked with a painter, Nathan Elder, who I interviewed on my Substack. Artists like Nathan have been applying this ladder to their own fields and finding resonance. Which has been a cool and unexpected development (for that reason I’m thinking of renaming it the ladder of poesis, poesis meaning creativity). In conversation we placed him at the Iconoclast stage (part of the scholar category). Iconoclasts like David Bowie advertise themselves in their art constantly, right? They turn themselves into a symbol.

So I pointed that out to Nathan. He was enthused and wanted to learn more. Some artists want to learn more about their stage and the system. Others are ok with just the key points. It just depends on what the artist needs. There’s no ‘one’ way to engage with the system. That’s the point of it, to meet the various needs of different artists and their approaches. Like a courtyard. But anyway, it clicked and ever since Nathan’s been on a creative roll. Not just coming up with more ideas, but, in his words, “his style as an artist has cohered.” He knows what he’s about now. His works of art (still-lifes of everyday objects) have become more crazy and out there and more recognisably him. He created a coffee pot wizard figure the other day and said it was the happiest he’s been with a work. So that’s been cool to see. Others might use the system in a more practical way. Scholars can aim to use more extended metaphors, try forms they haven’t tried, etc. It’s a way of reflecting and taking stock of one’s approach. So it has a lot of different effects. I’m still exploring them all!

G. K: At its heart, poetry is about resonance — that immediate, bodily recognition when language strikes something true. Can a system that analyses the creative process also deepen that emotional experience? Or is it more a way of seeing the process from a philosophical distance?

Isaiah:

I think it helps deepen the emotions of reading art. Because you get a sense of what the poet’s trying to do. If they aren’t trying to blow your socks off with the technical side of things, but are just looking to convey an emotion sincerely, then you can block out that other stuff. Or the other way around, if something is super technical, an “aesthetic artefact” as the scholars call it, then you can tune into that side of it also. It’s a way of reminding poets to think about the differences in approaches. You can and should read in all sorts of different ways though! That’s what poetry’s about. Maybe it’s old-fashioned of me, but I think there’s something nice about getting it on the level the poet intended first before I do my creative thing with it. Maybe because that can open us up to ways of engaging with a poem that’s not our usual preference. So that it expands us, or gives us a new frame, like poetry should? Just an instinct.

G. K: You’ve spoken about wanting to build a community around this idea. If you could speak directly to a poet reading this who might be skeptical, as I admit I am, what would you tell them? Why should they care about mapping what many of us have long accepted as unchartable?

Isaiah:

I would say that we poets don’t like borders and boundaries, for good reason. They don’t have the same place in art as they do in politics. But there are good laws in nature. Like clouds. They seemed chaotic for a long time. Then someone figured out the different types and suddenly there was order even in all the variations! All I’m saying is that there are some pretty big differences in poetic and creative approaches (compare, for instance, Shakespeare to the poetry of a heartsick teenage girl), which we can map. And that knowing this can help you to own your thing and figure out other peoples’ thing. I think that that’s good because it makes us a bit more complex. But a map that doesn’t lead to more engagement with the territory is a bad map. The poetry is the point! And if the system has any beauty, that comes from the beauty of poetry. Like the moon borrows the light of the sun. That seems suitably poetic.

Editor’s Note:

Speaking with Isaiah, I was struck by how his framework refuses to flatten art into theory instead, it opens it outward. The Ladder of Poetry isn’t a prescription; it’s a mirror held up to the many ways poets seek meaning.

His work is a reminder that the architecture of poetry is not a cage, but a cathedral — one built from intuition, intellect, and devotion.

Further Reading:

About Isaiah Freeman

Isaiah Freeman is a poet and English teacher based in Fremantle, Western Australia. Poetry and teaching are his two passions, and teaching poetry blends them together. He is building a community around The Ladder of Poetry and collaborating with artists to help them understand the uniqueness of their own creative drive.

If interested, he can be reached at 📧 ladderofpoetry@gmail.com and messaged through 📬 Essential Poetry on Substack

Bound Voices is a continuing interview series from Ink & Ribbon Press, a nonprofit publisher devoted to craft, discovery, and the permanence of the printed word.

Subscribe to The Inkwell for more conversations with poets, translators, and thinkers shaping the art of language today.

Great piece. Truly enjoyed the flow and direction.

Interesting, I'm not sure I quite follow the column of senses being attributed particular sense to particular style, perhaps I'm reading it wrong